Halloween Ends is Desperate to Remain Apolitical. At What Cost?

On the Halloween franchise, Michael's violent legacy, and "peculiar politics."

When I first read, in the YouTube description of a teaser trailer, that Halloween Ends would feature a young man who becomes an acolyte of Michael Myers, I thought I had it all figured out: This young man, I envisioned, would be a Michael Myers superfan, probably a copycat who either competes with Michael or gets taken under his wing (or both). He’d be someone who grew up in Haddonfield hearing the stories of the massacre, or maybe a message board troller from far away who traveled to Haddonfield to get as close to Michael (and Laurie) as possible.

This imagined plot checked all the boxes in my head. Laurie would have to reckon with Michael’s legacy and long-lasting impact on Haddonfield (and possibly the world at large). The town, fresh from the mob violence of Halloween Kills, would have to reckon with the consequences of their actions and perhaps make some hard choices about how to handle another killer (this one without death-defying superpowers). The nature of Michael’s devastating effects on the townspeople and how he siphons power from violence, death, and fear would finally be explained, or at least developed in some detail.

What we got instead—well, it wasn’t that.

Halloween Ends mostly follows Corey Cunningham (Rohan Campbell), a shy, awkward twenty-something traumatized by the accidental, gruesome death of the kid he babysat on Halloween three years ago. Corey is shunned by the town and beat up by high schoolers wherever he roams, but he maintains a gentle sensibility that appeals to Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis), his fellow Haddonfield outcast. Laurie sets him up with her granddaughter Allyson (Andi Matichak), who Laurie been living with since Allyson’s mom—Laurie’s daughter Karen (Judy Greer)—was killed by Michael Myers (James Jude Courtney) at the end of the 2018 massacre.

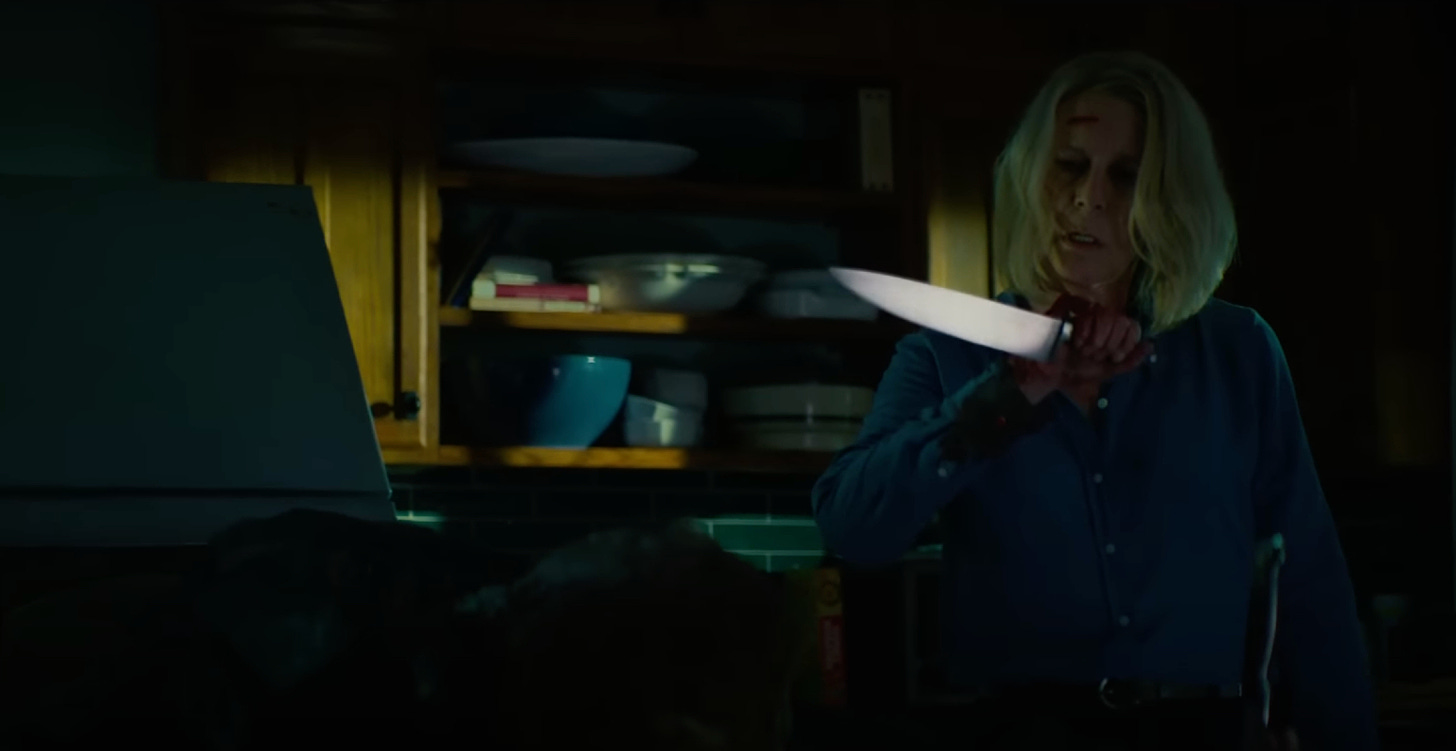

In the four years since that night, Laurie has recovered nicely. She’s sober; she’s knitting again (without intent to use the needles as a weapon); she’s baking pies—poorly, mind you, but it’s the thought that counts. Now, she lives in town and celebrates Halloween. She’s writing a cathartic memoir about survival. After all these years—indeed, after the infamous cliffhanger in which Michael kills Karen, then Laurie leaves the hospital to chase after him with a knife (after which apparently absolutely nothing of interest happens for four years)—she has finally embraced life in Haddonfield once again.

If only Haddonfield could embrace her back. The townspeople, it turns out, now hate Laurie.

The unnamed sister (Leila Wilson) of Sondra Dickerson (Diva Tyler)—who Michael attacked alongside her husband in Halloween Kills and who seemed very dead at the time but is alive and severely disabled by her injuries—confronts Laurie in a grocery store parking lot: “You tempted and you provoked that man when you should have left him alone.” Local shock jock Willy the Kid (Keraun Harris) insists on air that Laurie “harassed a brain-damaged man” and is thus responsible for the last massacre. Her friendship with Corey dissolves as quickly as it began. Eventually, even Allyson (briefly) turns against her grandmother.

Why, then, does everybody hate Laurie so much? We know she’s not great at maintaining relationships; she’s twice divorced, and in the most troubling non-horror scene of 2018, she shows up drunk to a family dinner and nearly destroys her relationships with her daughter and granddaughter once and for all in one fell swoop. But this isn’t that. It’s not Laurie’s fault that she’s been stalked, harassed, and attacked; it’s not her fault that her attacker killed dozens of people. It boggles the mind to think that a whole town full of people could come to the conclusion that it is.

Michael’s mysterious, damaging effect on the town is discussed at length in Kills. He’s the moral sickness that turns people against each other, that breeds mistrust and suspicion. He’s the shadow, the very Shape of fear. It stands to reason that he could be responsible for turning the town against Laurie, whether by draining energy from the townspeople like an emotional incubus or by somehow instigating or encouraging a campaign of misinformation about her role in the massacres.

The only problem is that he’s obviously not doing that. He’s weak, clinging to life in a sewer, not out sowing discord in the town square as he was in the previous film. Obviously, the nuclear fallout of his existence rains incessantly over Haddonfield, but at this point, even Laurie has tried to move on. He apparently hasn’t killed in years. How could he be directly fomenting resentment?

The pure absurdity of the near-universal animosity towards Laurie reminds me a little of the Scream franchise, wherein people are constantly calling Sidney Prescott a drama queen and an attention seeker for the crime of being targeted constantly by murderers of varying relation to her (boyfriend, half-brother, cousin, deranged fan/hater, etc). But one major difference between Sidney and Laurie is that most of Sidney’s killers are obsessed with her; they tell her so in great detail. Nobody knows exactly why Michael comes after Laurie. That’s the scary part.

A premise that added some intrigue to Halloween (2018)—that Michael doesn’t actually care anything about Laurie, and she just happens to keep being in the way—turned to mush in the next two films. If Michael doesn’t have any remote interest in Laurie, then I suppose the townspeople are right that it might seem like she’s provoking him. But she isn’t. Apparently, they just keep stumbling into each other.

This explanation is an obvious attempt to avoid the brother conundrum set up by Halloween II and painstakingly, headachingly attended to in every pre-2018 sequel. One could imagine a middle ground. He doesn’t have to be her brother, or trying to kill her in service of a cult; he could just be stalking her. If he doesn’t even care enough to truly stalk her, then why would he bother to turn the town against her?

He didn’t; he hasn’t. Michael really has nothing to do with it. It’s the very mechanism of the town, its rumor mill, its long-simmering fears, that has created this resentment against Laurie. The townspeople are doing it to themselves. But the question remains: Like, why? One possible explanation is that the spread of misinformation, especially when taken advantage of by opportunistic fearmongers, usually leads to scapegoating of vulnerable people and/or populations, or of people who merely remind you of the thing you fear. This could be an interesting continuation of the previous film’s mob mentality commentary: If you’re not careful, you might get swept up in something dangerous.

Okay. Sure. But Halloween Ends doesn’t say that. It doesn’t even really hint at it.

In fact, in its hesitance to resemble or represent any real-life political happenings (where else might we see large groups of people spouting nonsensical hatred based on lies and/or fundamental misunderstandings of how the world works?), Ends halfway implies that maybe Laurie is responsible.

Meanwhile, Corey’s relationship with Allyson blossoms rapidly. She’s very forward (in a way that, notably, seems very unlike the Allyson of the previous two films) and within just a few days, they’re inseparable: riding on a motorbike together, snuggling in a diner booth, confessing murder secrets to each other, plotting to leave town in a blaze of glory. It’s the kind of Sid and Nancy, Bonnie and Clyde relationship that’s meant to leave viewers unsettled. The problem is, when the hell did Corey become Sid Vicious?

He starts off nothing more or less than a sweet kid in an awful situation. Frank Hawkins (Will Patton) vouches for him to Laurie. Nothing in the first forty minutes of the film indicates that he has the remote capacity for actual violence or cruelty, even when he’s panicking or being actively beaten up. Maybe he’s got some repressed anger about his lot in life, sure, but the problem seems to be that he’s prone to turning it inward, harming himself.

When he meets Michael, that all changes overnight—literally. He’s pushed off a bridge by the aforementioned high schooler bullies; wakes up in a sewer; gets briefly strangled by Michael, who lets him go after he has some flashbacks/visions to traumatic events from his past (whether Michael actually caused the flashbacks somehow we’ll never know); kills an older, houseless man in seeming self-defense; and for the rest of the movie, he’s bitter, angry, violent. Suddenly, he loves killing.

Part of the issue is that it’s just not clear what exactly is going on between Michael and Corey. Did Michael possess Corey? Did the spirit of evil within Michael possess Corey? Did Michael awaken some evil in Corey that was already present? Did the terror of encountering Michael finally send Corey off the precipice over which he’d been hovering ever so precariously?

In order to answer these questions, Halloween Ends would have to establish some ground rules for Michael’s powers, which it’s unwilling to do. In a desperate bid not to rehash the Cult of Thorn plotline (speak of the brother conundrum), the new Halloween trilogy thrashes wildly between “he’s just a man” and “he’s not a man.” Even if Michael does have some sort of supernatural energy source—which, given that Halloween Kills implies that he literally gains power from the act of killing, he almost certainly does—it’s never remotely explored what that source could be. Halloween Ends drops that thread completely, until it’s convenient for half-explaining Corey’s sudden change in personality.

Regardless, Corey’s motives are fuzzy. His family life is unsettling, but not explicitly abusive. He genuinely seems to like Allyson, but on occasion it appears he’s only using her to taunt Laurie. The babysitting incident was a genuine accident. None of it explains why a chance encounter with Michael would send him on a murder spree.

What’s missing from Corey’s arc, then? Agency. Responsibility. Here, best case scenario is that Corey has been literally possessed by the spirit of evil; worst case scenario is that it’s not his fault he loves murder now because people were so mean to him when he did it by accident. Either way, he didn’t really choose to become Michael’s sidekick. A version of Corey who clearly and actively chose to side with Michael, whether out of desperation, pure love of the game (murder), or something else, would have been much more interesting.

Most obviously, Corey is not Michael. Corey kills several people because they hurt him or, more significantly, Allyson. Michael doesn’t kill people just because he has grievances with them; in fact, Michael doesn’t really have complex interpersonal grievances beyond annoyance. If he does have a motive beyond you got in my way, it’s usually psychosexual obsession with an object of twisted affection: his sister Judith; (arguably) Laurie. (We could certainly bring Jamie Lloyd into the conversation, but we won’t.) Where Corey is angry, Michael is impassive. Where Corey is particular, Michael is indiscriminate. Where Corey is subject to accidents, Michael is intentional.

Then again: It’s not clear whether any of that is on purpose, or what it adds. As we’ve established, these contradictions make for a pretty messy story. So what if he was Michael? Or, at least, what if he really, desperately wanted to be?

Here’s where I subject you to my second hot take: Corey Cunningham should have been an incel.

As much as we know anything about Michael, we know that he hates women; he hates nudity; he hates sex. That hate seems to take the form of a fear-based resentment, at least initially (consider his first murder: sister; naked; boyfriend).

Not much would make a lot more sense, then, than his gaining an obsessive fan who feared, hated, and resented women and female sexuality. Realistically, Michael would have legions of fans—specifically the young, white men who dream of committing violent acts against women—on websites like 8chan. And it would stand to reason too that—in an era where men like this write manifestos detailing their hatred of women, queer people, people of color, and religious minorities before committing acts of mass violence combined with a world in which Michael Myers is a genuine historical figure—eventually one of those people would try to pull a copycat crime.

Alas, the Halloween franchise is spooked by two things: 1) the internet; 2) social commentary.

I sympathize with the franchise’s reluctance to acknowledge the existence of the internet. The last Halloween movie before 2018 was Halloween: Resurrection, widely considered to be both the worst of the franchise and one of the clumsiest depictions of the internet ever put on film.

In 2002, when Resurrection was first released, the internet was still essentially a novelty. Now, it’s part of daily life (if not, for some, the bulk of it). It’s also been exactly twenty years since Resurrection. Imagine a spiritual successor that not only hit on a decade marker but finally, successfully used the internet to its advantage.

I admit, it’s hard to pull off. The closest we’ve gotten so far is probably Scream (2022), where it’s eventually revealed that the killers met on a Stab fan subreddit and plotted for months to get close to their targets. Before she’s shot, one killer screams that it’s not her fault; she was “radicalized.” Though the explanation is a little underbaked, it’s certainly compelling: Scream has always been about the ways that film fans interact with media, so of course the updated version addresses online fan communities.

Halloween isn’t Scream. That much is certain. But Michael is, for now, the last man standing among the great slashers: Freddy hasn’t appeared onscreen since 2010, Jason since 2009. A generation of real young men have glommed onto these killers as icons, role models. Why not reckon with the impact they’ve had on horror films and fans? Why not continue the critique of true crime in which Halloween (2018) seemed genuinely interested? And why not really explore the way the world has changed since the last time Michael came around?

Well, you might say, what about Allyson? Can’t be an incel with a girlfriend!

I’d argue that Corey and Allyson’s romantic plot, no matter how much time is spent on it, just isn’t necessary. Its impact on Allyson’s arc is simply bizarre; she feels like a completely different character than the high-achieving yet rebellious-in-a-normal-way teenager of the last two films. If the trauma of losing her parents and friends is supposed to explain it, the film doesn’t seem at all interested in developing that idea. Instead of forcing her into the role of Girl Who Rides On the Back of a Motorcycle, the movie could have spent its energy on developing Allyson’s other plotline: being harassed by a creepy guy she used to date but is no longer interested in.

I don’t mean that we need more of Allyson’s cop ex, Doug Mulaney (Jesse C. Boyd). We got, I think, exactly the right amount of him. But consider: During the scene in which Doug and Corey get into an argument at the diner, Allyson cowers in the corner, looking away from the action. I thought for sure she would get up and leave, giving them both a fuck you, if you can’t behave like adults, I don’t want either of you. She doesn’t. She just asks Corey if she can help him burn it all to the ground.

Let’s say, instead, Allyson does leave. What happens then? Corey’s plotline might start to develop some parallels to Doug, giving him a purpose beyond “get murdered” (and giving his kill some weight). Corey might take his place as the guy who’s effectively stalking Allyson—though he insists he isn’t. His rage, possessiveness, and misguided protectiveness might start to make a little more sense.

Ends, though it comes down admirably on the side of “murder is probably always bad,” wants badly to justify Corey’s anger. But who cares if his anger is justifiable to the audience? In order to start killing, he only needs to justify it to himself. (Besides, absent of some weird sequel territory, Michael has never needed to justify his killing. He just does it.)

In a post-Columbine landscape where school shootings by forum-radicalized young men are the norm, again, I understand the impulse not to want to touch the issue with a ten-foot pole. But you can’t embrace some real problems—just to list some that come up in 2018: violence against women; long-lasting and intergenerational trauma; the ethical concerns of true crime—and pretend you’re above addressing others.

Ends, it seems, is scared to have too much of a point. Maybe that’s the brother conundrum fear resurfacing again—an anxiety that trying to accomplish too much will lead to more nonsensical plot developments they’ll spend decades trying to dig themselves out of. Or maybe it’s the fear that, within their two mainstream audiences of devoted horror fanboys and middle-aged, white, moderate moviegoers who want to check in on the franchise for the first time in a few decades, politics won’t sell. It’s not arthouse cinema; it’s a slasher. Turn up the gore. Kill a dumb blonde.

In a 2021 interview, director David Gordon Green claimed that Halloween Ends would somehow tackle COVID-19 and the “peculiar politics” of the contemporary moment. Those elements are completely missing from the final draft, and the absence is palpable. What politics could Green be referring to but QAnon, and/or anti-vaxxers, and/or mass killings and gun violence? And what do all these phenomena have in common? A refusal to acknowledge the world as it is—a deep, abiding wish to return to a before, a normal that probably never existed.

I can imagine a lot of ways that Halloween Ends might have engaged with that desire, with the lies that get us there. I can also see that, in its final state, Ends ends up engaging with that desire in the sense that it tries very hard to finish off a version of the Halloween franchise that, really, never was.

Horror films (especially slashers) have always been about gender politics, from 1960’s Peeping Tom to Ti West’s recent X trilogy, with the original Halloween chief among them. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre’s Sally Hardesty may have come first, but Laurie Strode perfected the final girl. She screams and wails and cries; she wears a schoolgirl skirt; she stabs with phallic and/or domestic objects; she’s a babysitter.

As film scholar Carol J. Clover writes in her 1994 classic Men, Women, and Chainsaws (the book in which she invented the concept of the final girl), identification with both the killer (particularly in the case of Michael Myers, whose eyes we frequently see through) and the final girl necessarily transcends gender. A male viewer might come in expecting to identify with the violent, masculine murderer and leave identifying with the triumphant, androgynously named, phallic-weapon-wielding girl hero who defeats him. The final girl is a long-standing trope for two reasons. One: We love to watch girls and women suffer. Two: We love to watch girls and women go up against an impossible threat and win.

So if the final girl doesn’t threaten the horror fanboy or the mainstream moderate viewer—and it seems she doesn’t, given that she’s remained so popular over time—then why go further? Halloween (2018) lets Laurie win and keep winning—a hard-earned, bootstrapping, apocalypse prepper kind of win. So what if she’s been traumatized for forty years? She beats him, fair and square. An apolitical (that is, Libertarian) wet dream.

“The Halloween movies aren’t political” isn’t a good excuse. Of course they are. It can’t be avoided. And it seems that when you try to avoid it—as Halloween Ends so desperately, desperately does, despite Gordon’s apparent plans—you effectively kill the story.

The weight of contemporary politics and current events might have helped balanced the film’s plot, thus balancing the trilogy as a whole. It also might have helped the trilogy say something about the legacy of Michael Myers, the pain he caused, or the people who survived and overcame it. In its hurried quest to close Laurie’s chapter, Halloween Ends manages to say nothing about anything—not Michael, not Laurie, not Haddonfield, not the franchise, not the real world. Its messages, if there ever were any, get muddled to the point of incoherence. It remains completely ideologically inoffensive and bland. It’s ultimately about nothing. Maybe it would have just been easier to say something instead.